The delivery room was quiet. It was not what Amanda Miller had expected moments after giving birth. She had envisioned laughter and happy  chatter as she cradled her baby boy, Jayson Andres Miller, and posed for pictures.

chatter as she cradled her baby boy, Jayson Andres Miller, and posed for pictures.

Instead, there was underlying tension. Jayson wasn’t crying the hearty cry of a newborn. At first pediatrician Jennifer Altman, MD, who was on call that day at Sentara Williamsburg Regional Medical Center, thought it was due to exhaustion. The delivery had been tough for both mom and baby.

But something else bothered her more than Jayson’s passive cries.

“His coloring wasn’t right,” Dr. Altman says, “and when I checked his oxygen saturation levels, the oximeter flashed 30 percent. He had good respiratory effort, but that number was so low that I thought for a brief second there must have been equipment failure.”

Realizing something was seriously wrong, Dr. Altman let Amanda see Jayson for a moment and then called Children’s Hospital of The King’s Daughters.

As CHKD neonatologist Susannah Dillender, MD, listened to Dr. Altman’s assessment, she thought back to her fellowship training.

“One of the first patients I saw had Transposition of the Great Arteries,” Dr. Dillender says. “And Jayson had all of the classic indicators.”

CHKD rushed a transport vehicle to Williamsburg. By the time the transport team arrived, Jayson’s pulse oxygen saturation level had dropped to 26 percent. “I was very concerned,” says transport nurse Karen Callaway, RN. “He was gray when we got there.”

“My biggest fear was that Jayson wouldn’t be able to hang on,” Dr. Altman adds.

“My biggest fear was that Jayson wouldn’t be able to hang on,” Dr. Altman adds.

The transport team stabilized Jayson and began medicating him. “By the time we left for CHKD he was pink and his saturation level had climbed into the 80s,” Callaway says, “good news for the trip to Norfolk.”

While Jayson was being transported, Dr. Dillender was busy assembling a response team for his arrival. She remembers the team “was on pins and needles in anticipation of saving this baby.”

Meanwhile, Jayson’s family was battling heartache and fear.

“There were a lot of unknowns when they transported Jayson to CHKD,” says Rey Cofresi, Amanda’s father. “He weighed 9 pounds, 8 ounces, and we thought he was a big, healthy baby.”

The two-hour wait to learn what was wrong felt like an eternity to Jayson’s dad.

“This just isn’t something you think about when you’re heading into the delivery room after a normal pregnancy,” William Miller says. “But when you’re following an ambulance to CHKD, you think about a lot of things.”

After Jayson arrived, CHKD cardiologist John Reed, MD, confirmed Dr. Dillender’s instincts about the diagnosis: Jayson’s aorta and pulmonary artery were transposed, a congenital condition that affects only about five out of every 10,000 babies. Jayson’s aorta ran from his heart to his lungs when it was supposed to go from his heart to his body. And his pulmonary artery was doing what his aorta was supposed to do. For the newborn to survive, both would have to be surgically corrected.

Next, CHKD cardiologist Elliot Tucker, MD, was brought in. Dr. Tucker’s task was to give little Jayson a few days to settle before surgery. “If possible, we want to avoid open-heart surgery on a baby who is only a few hours old,” he says. “Performing a balloon septostomy would give Jayson more time to be a better candidate for major surgery.”

Dr. Tucker’s balloon septostomy involved inserting a catheter into the vein in Jayson’s upper thigh and snaking it up to his heart. A newborn naturally has a hole between the heart’s left and right atria. It is there to allow the mother’s oxygenated blood to flow freely through her baby in the womb. But once the baby draws its first breath, the hole begins to close. Dr. Tucker’s duty was to increase the size of the hole and keep it open, which would allow more of Jayson’s oxygenated blood to make its way to his body until he was strong enough for surgery.

“There comes a point where you put your faith in the doctors, brace for the worst and hope for the best,” Cofresi says.

Jayson’s transposed arteries required open-heart surgery when he was just three days old.

Jayson’s next major step would be handled by Dr. M. Ali Mumtaz, CHKD’s chief of cardiac surgery, and his surgical team. Through delicate and complex open-heart surgery on Jayson’s third day of life, Dr. Mumtaz switched the routing of his aorta and pulmonary arteries, allowing the infant’s blood to oxygenate properly and flow through his body.

While his open-heart surgery was the final – and most major – step of Jayson’s treatment, Dr. Mumtaz was elated with the outcomes of all the steps that had come before his.

“The fact that Dr. Dillender had a very strong suspicion that we were dealing with Transposition of the Great Arteries set this success story in motion,” Dr. Mumtaz says. “In cases like this one, where the baby’s condition wasn’t diagnosed prior to birth, every minute counts.”

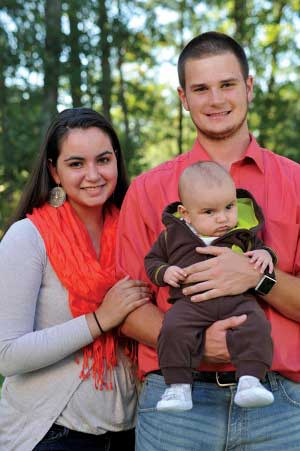

Today, Amanda and William have a new awareness of the importance of having CHKD within reach. Jayson is a happy, healthy 8-month-old because the expertise he needed from day one was just a phone call away. That call activated a whole team of professionals who focused on him and his family without fail, bringing the best possible care to their firstborn child.

Amanda was so moved and inspired that she decided on a career in nursing. “After all I witnessed with Jayson, I know I want to work in cardiology.”

Drs. Dillender, Reed and Tucker practice with Children’s Specialty Group at CHKD. Dr. Mumtaz practices with CHKD Surgical Group’s cardiac surgery practice. Dr. Altman practices with Sentara Pediatric Physicians in Williamsburg.

This story was featured in the Spring 2013 issue of KidStuff, a publication of Children's Hospital of The King's Daughters.